Previously: Britannicus the pamphleteer; Imogen the diplomat; Cymbeline versus Illyria; Cymbeline versus Innogen; Dr. Cornelius and his caller; Posthumus and the walls; Rigantona looks fondly on him; Imogen leaves on her own.

All of Londinium is my city, even the parts I haven’t seen yet. Behind us is the palace, the chieftains, the minders, the arrangements, the backrooms. Behind us is my father, whose greatest fear is that I will be out of bed.

We have the river between us now. Yes, it warms me a little. Maybe some. Maybe more.

This is my city, day and night. It will open to us if we ask.

*

“I say, I say, I say! A girl for that other arm, my lad? Fine-looking woman, two’s better than one, I say!”

Posthumus pulls me closer, stammering to the stout man who’s planted himself in our way. The fellow winks at me and tips his cap. “Or I got boys—you want two boys for your lovely lady there? Guarantee she’ll love it, bet you will too! Ten pieces for the first hour, prices negotiable after that.”

“I—thank you,” Posthumus tries, pushing up his glasses. A towering woman jostles us with an enormous, ragged bustle as she passes. I clutch my jacket as I catch myself, to be sure of my purse inside.

“We’re fine,” I say quickly, and lead Posthumus around the pander.

“It’s Bellicia’s Bawds when you change your mind!” he shouts after us.

Before I came to Sower Street, I might only have known this: that when the Romans built their great bridges over the Tamesis, fishers sold their bankside land to builders and moved on from fishing. That taverns, theaters and all manner of low entertainment bought deeds along the new road, and flourished like so many toadstools. That Sower Street is a byword in Britain for all the trappings of ill-spent money and youth.

Posthumus twists to stare at the pander, gobsmacked at the offer we just fled. “This was a better idea at the palace,” he says.

I have to smile, only a little. “Oh come now. Cloten is here somewhere—what’s that, if not a ringing endorsement?” I nod toward the long row of public houses, Romans and Britons alike streaming through the open doors. “Which one looks most appealing?”

“I’m not him,” he says, irritated. “Don’t start with that.”

*

I have accepted the fundamental madness of our childhoods, for which I’ve been granted some narrative consistency. Posthumus may not remember it, but that means nothing. Soldiers may black out the pitch of battle; survivors of a sinking ship may blot out their time in the water. A trauma like ours could easily leave no trace. A child might touch a machine and become two children. A girl might dream of it for years and learn it was true.

Cloten might know what happened that night at the exhibition. He was there too, and his mother who found him had to tell him something. We are not doing anything unreasonable, now that this is the case.

*

The Emporion, the sprawling port. Every surface plated with bright tiles from Massilia. Continental fare covers the tables, wine and olives and goat’s cheese and rosemary. One look and I’m ready to turn around. “He’s not here.”

Posthumus knits his brow. “He might have stopped in.”

Rigantona surely raised him calling us Lud’s-town. She believes in Britain. This place seethes with empire.

Posthumus catches a trim, dark man in a spotless apron. “Excuse me,” he says, one hand on his arm. “I’m looking for someone, my height, no glasses, curly hair.” The server glares and pushes past us. Posthumus tries to follow. “His name is Cloten. Has he been by?”

The server curls his lip and leaves us behind. At the bar, a smartly-dressed man, his black hair slicked neatly back, smirks into his tumbler. I am exquisitely aware of my scuffed boots and seasons-old skirt, of Posthumus’s knobby wrists inches beneath the sleeves of his coat. This place is aspirational; he wants to be here, not Cloten. All at once, I’m embarrassed for him. I grip the back of a nearby chair. “We can do better than this.”

Posthumus’s expression curdles, just a little. “I’m listening.”

You live at the palace, I want to say. Instead, I nod to the tiles, to the statues of the gods. “Let’s start with places where he wouldn’t come just to pick a fight.”

“Fine.” He dips his chin. “By all means, we’ll do it your way.”

I drop my hand. “That’s not what I’m saying—”

“Aren’t we wasting time?” he says, and strides toward the door.

*

“Can we be clear on one thing?” Posthumus steps to avoid a puddle of effluvia, pressing us instead into a hooting gaggle of wealthy teenage boys. “I need to know why you’re out here with me.”

“We need to find Cloten. Were you not sure?” I squeeze my elbows to my side, narrowly dodging a young man with much to learn about sharing space. “Remember we both had the same idea and met in the middle.”

Posthumus shakes his head. “I want to find him and see what he’s about. As far as I can tell, you just want to win at something.”

I smile. He’s needling because he can, because he’s nervous. “What do I want to win here?”

“You don’t like it that no one thinks your theory is wonderful,” he says. “You don’t like it that I haven’t said I believe you.”

My smile becomes tighter. “I don’t like that you’re less committed than I expected.”

“Soft beds up here!” someone calls from an open window. “No fleas! Good rates!”

Posthumus bows his head. “You’re telling me that I’m half of some other person. Forgive me if I’d rather take some time on this.”

Rigantona is not waiting for any of us. I can only laugh; I am out of other rebuttals. “What time have we got?”

*

Ardu, named for the forest without roads. The walls teem with hunting gear and taxidermy; no subtlety nor chance of escape allowed. The barkeep glowers, a gladiator in a starched shirt. His bald head gleams; his mustache bristles, perfectly trimmed. His arms bulge as he wipes down a mug that engulfs his fist.

“He’s not my brother,” Posthumus insists. “I’m just looking for him.”

The barkeep eyes me suspiciously. I give him a bland, eager smile. He grunts. “Strangers have no business hearing about my customers.”

I have coin ready; it gleams against the counter between us. “We’re customers too. Doesn’t that make us friendly?”

He pockets the money with not a flicker of interest and strolls off to the taps. Posthumus drums his fingers, engrossed with the wall art. The din of the pub rushes in to fill the space. Behind us, a cluster of men howls in a parody of song. A few seats down, a red lady leans against a shabby man, her hair threaded with the ribbons of her trade. Where her hand is is anyone’s guess. Posthumus appears, with effort, not to notice.

The barkeep returns with two tankards, one laughably dainty, which he sets before me. He grunts at Posthumus. “Left here about an hour ago,” he says. “I wasn’t sorry to see the back of him.”

I lean over the counter. He can be no harder to crack than a proconsul. “You don’t have any idea where he could have gone?”

The barkeep’s monstrous mustache twitches, but Posthumus cedes the man’s attention to me. “He didn’t confide in me. I’d guess further down the street.” He says so with rueful disdain, as one who knows that he’s low but not that low.

“He’s not my brother,” Posthumus insists, setting down his mug. The barkeep watches him, unimpressed. Posthumus glances at me, wipes his mouth and drinks again.

*

Three Cambrians cheer as we leave Ardu. “Lovely catch!” crows a ruddy fellow with one dead tooth. Posthumus tightens his hold around my shoulders.

“They’ve obviously seen him!” I hiss. “Let’s go back!”

“There’s nothing obvious about it,” he says, eyes forward. “They’re just catcalling.”

“I could give a damn. We have to talk to them!” I squirm out from under his arm.

He throws up his hands. “Yes, of course we do, Imogen, because after all, it’s your idea, and your ideas are never wrong.”

I circle in front of him and glare. “Would you shout a little louder, please? I don’t think the whole street heard my name.”

He rolls his eyes. “Oh, calm down.”

“Don’t, Posthumus.”

*

We cut across the current, across the street. On the curb, a young woman is bawling; another crouches next to her, rubbing her back. Drunks spill past us, laughing and baiting each other. We step to one side, not looking at each other, waiting for an opening. One of them catches sight of us. He’s a middle-aged man, shorter than I am, half bald with a merry face. He beams. “Here now. Haven’t I seen you before?”

“I think you’re mistaken,” says Posthumus, at the same time I say, “Him? Have you seen him?”

“No. No no no.” The man veers closer. “I know I’ve seen you before.” He wags a finger. My breath catches. “Down on Epaticcus Lane, eh? Here on your own time, then?” He reaches for my arm.

In an instant, Posthumus has stepped between us. He has a good eight inches on the man. I cannot think of Posthumus as ferocious, but in that moment, he is so still, I wonder what he might do.

“Too early for a fight, Mato.” One of his friends pounds his shoulder and pulls him back. Mato gives me one more merry wink before he’s swept off down the street.

“This is all a mistake,” Posthumus murmurs, neck bent.

“Let’s not catastrophize.” I slip my arm through his again. I also look behind us, watching Mato, weaving away.

*

The Boar and Brachet, wild pigs and hounds crowding every inch. Posthumus cocks his head. “Isn’t it the Gauls who are obsessed with boars?”

It’s an old place, all the wood dark and stained and smooth. The booths are pitted with nicks and dents, deeply gouged with graffiti. The names and boasts are all British; not a hint of Latin to be seen or heard. A proud place. For a princess of Britain under Rome, an oddly uncomfortable place.

Posthumus has gone still again. Of course he has: abruptly, there is Cloten, raising his glass to a group of regulars.

He is hard to watch. He goes from chair to chair, the dog wagging furiously and hoping for scraps. I still can’t reconcile the movements he makes with the face and the body he wears. His expression shifts constantly, often exaggerated, often unpleasant. I glance at Posthumus, who is so quiet I hope he will come up for air.

“We should get him,” I say quietly.

Posthumus looks at me, skeptical. “It’s noisy, it’s raucous, the night is young and so are we—what do you think you’re getting from him tonight?”

“He’ll talk to us,” I insist. “This is important.”

“Imogen, this theory of yours, I’m not even sure I believe you yet.” Posthumus slips his hands in his pockets and looks out over the bar. Then: “I’ll get him.”

“Why don’t we both—”

Posthumus shakes his head. He’s in earnest. I glance toward the bar again, uncomfortable. “You don’t like each other.”

He doesn’t look away. “Let me have this.”

Posthumus is here for a different reason than I am. If I am honest, I have no rebuttal.

He leaves me at a booth that hasn’t been cleared yet. I slide into the middle of the bench and try being patient. One hand starts tugging at the fingers of the other. The noise of Sower Street is starting to bear down on me. I jump at an unseen burst of laughter. At another table, a handful of sailors whistle at me. When I look up, one of them makes grotesque kissing faces; another waves me over. I swallow. Posthumus has left me alone with my city. Realizing I don’t feel safe here infuriates me.

The Greeks have a name for everything. In one word, they describe the act of descending into the underworld: katabaino. Perhaps tonight is making me heavy-handed. I think we’re at the rim of something we can’t see the bottom of.

The pit of my stomach boils, watching Posthumus’s slow collision course with his double. Cloten has shed his jacket and rolled his sleeves to the elbow, loose-limbed and gregarious; Posthumus is shabby and contained, pushing politely through the throng. I wonder, in that moment, precisely what parts of him went with Cloten when they split.

I brace myself for tension, more of the spitting cats from our encounter near the Pallas. Instead, Cloten beams and crows “Posthumus Leonatus!” before thumping him on the back. He embarks on a ramble, full of gesticulations. The regulars lose interest. Posthumus leans close to him, and then points toward me. Cloten’s face lights up with that leer. My jaw goes tight. He swipe his coat from a stool and marches toward the booth, Posthumus at his shoulder. I slide to the outside edge of the bench: he’ll have no chance for liberties.

Cloten plants both hands on the table in front of me. “Who’d have thought to see you here?” He grins. “You have any more surprises for me tonight?”

He reeks of curmi, the cheap barley liquor. Posthumus hovers behind him. To see them side-by-side is still dizzying. I lift my chin. “Have a seat.”

Cloten needs no further obliging; he throws himself down the bench. Posthumus lowers himself next to him, corralling him by the wall. I fold my hands. “Cloten, we’re so glad we found you.”

“Aren’t you?” He smirks, and slings an arm over the back of the booth. “I knew you couldn’t keep away from me.”

“That’s not what she’s saying,” Posthumus begins.

He reaches for his shirt buttons. “I was going to woo you first, but hell, if you’re eager, I’m willing—”

“Cloten,” I interrupt sharply. “This is important.”

He pounds the table. “By all means, then, another round!” He splays a hand over the table, then counts each finger. “I have been at this for five hours now. Let me elucidate you, it only gets better with more.”

*

Cloten plants his chin in his palm. “You came for me,” he says dreamily. “How many times?”

“Mind yourself,” says Posthumus sharply. “She’s going to be queen one day.”

Cloten wags his eyebrows, a senseless jackal just before he laughs.

“Enough.” I shift toward the edge of the bench. “Cloten, we have questions for you, personal questions. Let us take you somewhere, we can make sense of some things.”

“Why, what is it we can’t do here? Other than the expected. I’ve already been reprimanded for that.” He slings an elbow around Posthumus’s neck. “I feel so close to you already—”

“He’s not your brother!” I snap, unplanned and more passionately than intended.

Cloten wrinkles his nose. “Who’s saying that?” Posthumus watches me while carefully disentangling himself from Cloten’s arm. “You know, we both made mistakes tonight.” Cloten’s mouth twists, ugly. “You left your father with my mother, and I left my mother with your father.”

Posthumus frowns. “She’s working for the king.”

Cloten twists toward him. “Have you ever worked a queen?” He winks at me. “Or a future queen?” He claps a hand on Posthumus’s knee. “You should if you haven’t tried.”

My cheeks are hot. All my foolishness is smacking me in the face right now. Everything we’ve learned tonight could have waited another day. “Watch yourself, Cloten. You won’t remember this in the morning, but I will.”

“Save your breath,” he sneers. “This isn’t the palace. None of this matters and no one cares.”

“Listen,” says Posthumus quickly, glancing at me, then turning to Cloten. “Why not take a walk? Get some fresh air?”

Cloten points at him. “You have an interest in asking me nicely.”

“We both do,” he says. “Come on, there’s no reason we can’t all be friends.”

Cloten thumps both elbows on the table. “I like him,” he says to me. He sniffs. “So what if he’s poor and half Roman? I wish you could be more like him. Wait, this is a good one!” He hunches low. “Have you got any Roman in you?”

Posthumus sighs. “Don’t answer that.” He stands and buttons his jacket. The sailors start to howl and whistle.

“Are we going?” Cloten blinks. He waves lazily at the churning pub crowd. “Forget all this. I know a back way out. Forgive me if I’m not precise—I was distracted when the lady showed it to me.”

*

We’ve come only to make him trust us. We follow him, past the brewing vats, past the kitchens, out the delivery doors, into the alley and past the men urinating on the bricks. Posthumus and Cloten walk sometimes shoulder-to-shoulder, sometimes drifting into a line. The rhythm in their movements is nothing alike: Posthumus upright, steady; Cloten swaggering, meandering. How different they became. How queasy to see them together.

The alley runs parallel to the street—to be expected, but so far we can’t seem to find a way back, save through other pubs. I glance at Cloten, hoping he hasn’t led us totally astray. There’s something haggard in his face under the cider cast of the gaslamps. He’s coiled tight and in his cups, which makes me warier than ever. “Are we close?” I ask, hoping one or the other will answer.

Cloten stops and looks around, his face blank. Posthumus turns and points over his shoulder. “I’ll check up ahead.” His long stride takes him away from us before I can insist otherwise.

Cloten and I stand there by the trash bins of The Laughing Mare, awkward as unwilling dancers. The persistent roar of merrymaking is muddied back here, as is the silt smell of the river. “You came for me,” Cloten says thickly.

“We were impatient.” I glance up the alley, to check on Posthumus. “We think you might know something important.”

He shakes his head, something unspooling in his face. “No one ever comes for me.” Too late I see he’s closing the space between us. I sidestep him, but he traps me between his arm and the bricks. “Finally,” he slurs, and leans in, mouth open.

It happens so quickly. I twist away; his lips only graze my forehead. I catch the full force of his five hours of drinking, and gag. His hand gropes at my stomach, seeking higher than that. He tries to pull me toward him. “Oh no,” I grunt; I grind my teeth, brace myself and ram my elbow into his chest.

He staggers, wide-eyed, hanging midair for a moment before collapsing spectacularly into a stack of empty crates. His limbs go flailing. A rat shrieks and scuttles away, at which Cloten thrashes even harder. “What was that for?” he yells.

I raise both fists. “What do you think it was for?”

“Oh, that’s right,” Cloten snarls, grappling for purchase and toppling more boxes. “Never mind what my mother’s doing to your father right now. Never mind what a man wants for himself. It’s all the same whatever Cloten wants.”

Posthumus skids to a halt behind me. He checks in, a hand on my elbow, then takes a step toward Cloten, who shouts, “You stop pretending at me!” He rolls away from the mess he’s made and pushes himself to his full height. “I don’t need you,” he barks. “I’ll find better ones. To all the hells with both of you!”

He spins on his heel and marches, full speed ahead, two whole paces, where he collides, headfirst, with a thick copper pipe and lands flat on his back, dead to the world.

One of the men who’d been at the wall yells up the alley. “Hurt, love?”

I wrap my jacket as close around me as I can. I’ve gone cold with rage, shaking and breathing hard. Posthumus sets a hand on my shoulder. “We’re fine,” he shouts back.

*

Posthumus takes a step toward him. “Come on.”

I plant my feet. “Come on what?”

He stops. “We can’t just leave him there.”

“I don’t see why not.”

Posthumus just nods. “Fine. Go back to the palace. I’ll meet you there.”

My knuckles go white. “Don’t be absurd. I’m not leaving without you.” Posthumus lifts his eyebrows. I point to Cloten. “You’re excusing him?”

He holds up his palms. “No, I’m not—”

My voice quakes. “You were right, you know. There was no way we’d get anything out of him, now or ever.”

“That isn’t what I—“

“We’re done. I could honestly give a fig what happens to him.”

“You have stakes in this if I do,” Posthumus says quietly. I only listen because it’s him, it’s Posthumus, and he came with me tonight. “You’ve asked me to believe a lot of difficult things about Cloten and me. Either he’s as important as you say, or you don’t want to deal with what you’ve started.” We’ve both gone still now. “Tell me,” he says, “because it’s one or it’s the other.”

*

We drag him back toward Sower Street, toward the gaslamps, toward the hackney cabs. We carry him between us, deadweight over our shoulders. Cloten’s eyes flutter open. I ought to want to see him as Posthumus does, as related, as salvageable, but I can’t. I can’t and I won’t. Cloten laughs, unsteady and soft. “You’ve never come back for me before.”

Posthumus leans closer. “What was that?”

He releases a long, deep breath, a rotten wind. “My whole life, over and over again at night. I’m left there and I can’t see anything and no one ever comes back for me.” He trips, and Posthumus grunts as he props him up.

I hitch his arm up higher. “We came for you, Cloten.”

“It was just an accident,” he mumbles. “I caused so much trouble.”

“Yes,” I murmur, resenting his sour smell, the fact of my bearing him. “More than you know.”

“The lights went out,” he continues, and his voice cracks. “Oh, everything just went out, and no one came.”

An empty cab lurches in our direction. I hail it, certain it won’t slow down even after it hits us. The driver casts a jaundiced eye at us, but accepts us with our load.

“Well,” Cloten sighs as we push him upright into a seat. “She came for me. But she wasn’t angry long.”

“Say it again?” Posthumus settles in beside him, but Cloten is already snoring, open-mouthed.

*

I realize this as we are walking home, Cloten since deposited at his front step.

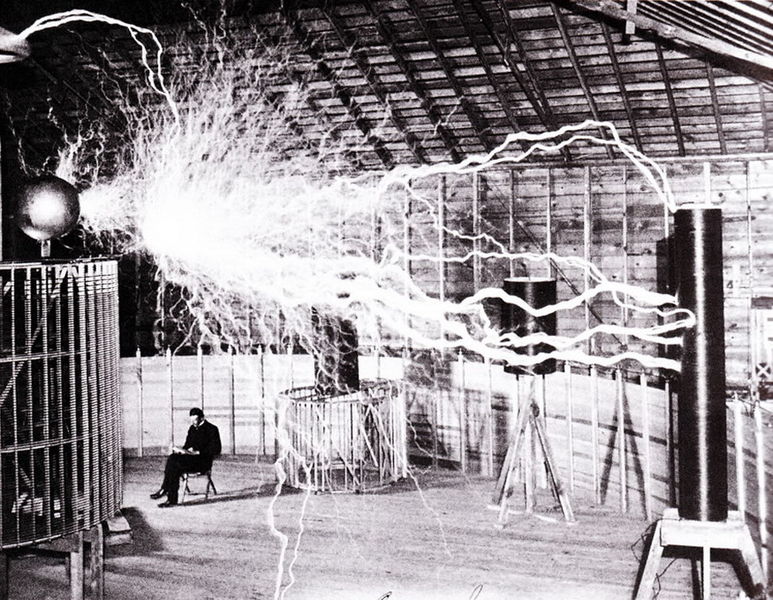

The nightmare will come tonight: the pearlescent glow, the air sucked out of our chests, the towering generator thrumming through the floor. Children can touch a machine and become two children. Posthumus has no such memory, but that is not proof against it.

“I did win,” I say softly. Posthumus looks at me, brow furrowed. Oh, for all the comfort it brings me. “It happened just like I’ve said it did.” I ball my hands in my pockets. “Cloten remembers.”

Posthumus matches me, step for step. “How can you tell?”

“He dreams it. He said so, on the way back.”

Neither one of us speaks. We plod on, quiet as the city around us, back to our beds in my father’s palace.

home | next: The heavens must still work

Hi, and thanks for reading! Got some feelings? I would love to hear your thoughts. All content © Esther Bergdahl, 2011. Thanks again, and hope you enjoy!